This may take up to thirty seconds.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Photography by Roman Vishniac, ca 1935-1938

This recently discovered vintage print includes an annotation in Vishniac’s hand, “Satu Mare,” referencing the town that is the seat of the Satmar Hasidic sect. Significantly, Vishniac’s photograph captures a relatively secular subject—a young woman in modern dress and hairstyle smiling directly at the photographer—in a town commonly associated with the most rigid observance of ultra-Orthodox Jewish practices. Although this is the only identified image of Satu Mare by Vishniac, it is likely that he took more than one shot during his visit, and that the archive contains other negative frames awaiting identification. This image and others like it contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the prevalence and intermixing of secular life in observant communities in Eastern Europe prior to World War II.

Copyright © Mara Vishniac Kohn

Gift of Mara Vishniac Kohn to International Center of Photography, 2013

"Wedding feast in Brześć nad Bugiem". Photo from the collection of the National Museum in Gdańsk, possibly taken by Józef Górowicz in 1933.

Rabbi Chazzan David J. (Koplowicz) Kane with his father, Karol Koplowicz in Będzin, Poland.

Będzin on an old postcard. View of the castle in Będzin and the synagogue at the beginning of the 20th century from the side of the Czarna

Until World War II, Będzin had a vibrant Jewish community. According to the Russian census of 1897, out of the total population of 21,200, Jews constituted 10,800 (around 51% percent). According to the Polish census of 1921 the town had a Jewish community consisting of 17,298 people, or 62.1 percent of its total population. In September 1939, the German Army overran this area, followed by the SS death squads, who burned the Będzin synagogue and murdered 200 Jewish inhabitants.

Prisoners building the Krupp munition factory (later Weichsel-Union-Metallwerke) next to Auschwitz IW. 1942 or 1943

http://auschwitz.org/en/gallery/historical-pictures-and-documents/life-and-work,8.html

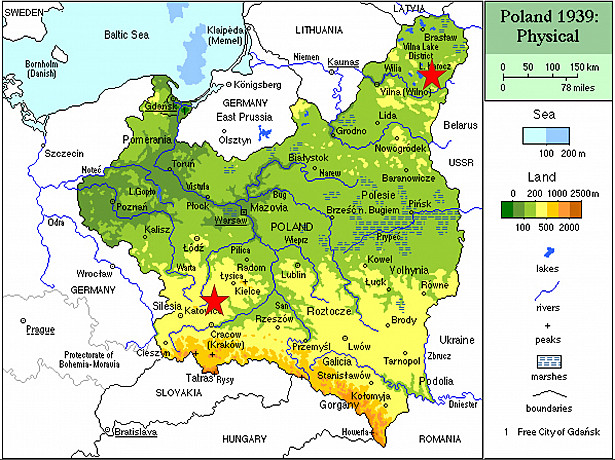

The newly independent Second Polish Republic had a large and vibrant Jewish minority. By the time World War II began, Poland had the largest concentration of Jews in Europe although many Polish Jews had a separate culture and ethnic identity from Catholic Poles. Some authors have stated that only about 10% of Polish Jews during the interwar period could be considered "assimilated" while more than 80% could be readily recognized as Jews.[86]

According to the 1931 National Census there were 3,130,581 Polish Jews measured by the declaration of their religion. Estimating the population increase and the emigration from Poland between 1931 and 1939, there were probably 3,474,000 Jews in Poland as of 1 September 1939 (approximately 10% of the total population) primarily centered in large and smaller cities: 77% lived in cities and 23% in the villages. They made up about 50%, and in some cases even 70% of the population of smaller towns, especially in Eastern Poland.[87] Prior to World War II, the Jewish population of Łódź numbered about 233,000, roughly one-third of the city’s population.[88] The city of Lwów (now in Ukraine) had the third-largest Jewish population in Poland, numbering 110,000 in 1939 (42%). Wilno (now in Lithuania) had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city's total.[89] In 1938, Kraków's Jewish population numbered over 60,000, or about 25% of the city's total population.[90] In 1939 there were 375,000 Jews in Warsaw or one-third of the city's population. Only New York City had more Jewish residents than Warsaw.

The major industries in which Polish Jews were employed were manufacturing and commerce. In many areas of the country, the majority of retail businesses were owned by Jews, who were sometimes among the wealthiest members of their communities.[91] Many Jews also worked as shoemakers and tailors, as well as in the liberal professions; doctors (56% of all doctors in Poland), teachers (43%), journalists (22%) and lawyers (33%).[92]

L. L. Zamenhof, creator of Esperanto

Jewish youth and religious groups, diverse political parties and Zionist organizations, newspapers and theatre flourished. Jews owned land and real estate, participated in retail and manufacturing and in the export industry. Their religious beliefs spanned the range from Orthodox Hasidic Judaism to Liberal Judaism.

The Polish language, rather than Yiddish, was increasingly used by the young Warsaw Jews who did not have a problem in identifying themselves fully as Jews, Varsovians and Poles. Jews such as Bruno Schulz were entering the mainstream of Polish society, though many thought of themselves as a separate nationality within Poland. Most children were enrolled in Jewish religious schools, which used to limit their ability to speak Polish. As a result, according to the 1931 census, 79% of the Jews declared Yiddish as their first language, and only 12% listed Polish, with the remaining 9% being Hebrew.[93] In contrast, the overwhelming majority of German-born Jews of this period spoke German as their first language. During the school year of 1937–1938 there were 226 elementary schools [94] and twelve high schools as well as fourteen vocational schools with either Yiddish or Hebrew as the instructional language. Jewish political parties, both the Socialist General Jewish Labour Bund (The Bund), as well as parties of the Zionist right and left wing and religious conservative movements, were represented in the Sejm (the Polish Parliament) as well as in the regional councils.[95]

Isaac Bashevis Singer (Polish: Izaak Zynger), achieved international acclaim as a classic Jewish writer and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978

The Jewish cultural scene [96] was particularly vibrant in pre–World War II Poland, with numerous Jewish publications and more than one hundred periodicals. Yiddish authors, most notably Isaac Bashevis Singer, went on to achieve international acclaim as classic Jewish writers; Singer won the 1978 Nobel Prize in Literature. His brother Israel Joshua Singer was also a writer. Other Jewish authors of the period, such as Bruno Schulz, Julian Tuwim, Marian Hemar, Emanuel Schlechter and Bolesław Leśmian, as well as Konrad Tom and Jerzy Jurandot, were less well known internationally, but made important contributions to Polish literature. Some Polish writers had Jewish roots e.g. Jan Brzechwa (a favorite poet of Polish children). Singer Jan Kiepura, born of a Jewish mother and Polish father, was one of the most popular artists of that era, and pre-war songs of Jewish composers, including Henryk Wars, Jerzy Petersburski, Artur Gold, Henryk Gold, Zygmunt Białostocki, Szymon Kataszek and Jakub Kagan, are still widely known in Poland today. Painters became known as well for their depictions of Jewish life. Among them were Maurycy Gottlieb, Artur Markowicz, and Maurycy Trebacz, with younger artists like Chaim Goldberg coming up in the ranks.

Many Jews were film producers and directors, e.g. Michał Waszyński (The Dybbuk), Aleksander Ford (Children Must Laugh).

Shimon Peres, born in Poland as Szymon Perski, served as the ninth President of Israel between 2007 and 2014

Scientist Leopold Infeld, mathematician Stanislaw Ulam, Alfred Tarski, and professor Adam Ulam contributed to the world of science. Other Polish Jews who gained international recognition are Moses Schorr, Ludwik Zamenhof (the creator of Esperanto), Georges Charpak, Samuel Eilenberg, Emanuel Ringelblum, and Artur Rubinstein, just to name a few from the long list. The term "genocide" was coined by Rafał Lemkin (1900–1959), a Polish-Jewish legal scholar. Leonid Hurwicz was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Economics. The YIVO (Jidiszer Wissenszaftlecher Institute) Scientific Institute was based in Wilno before transferring to New York during the war. In Warsaw, important centers of Judaic scholarship, such the Main Judaic Library and the Institute of Judaic Studies were located, along with numerous Talmudic Schools (Jeszybots), religious centers and synagogues, many of which were of high architectural quality. Yiddish theatre also flourished; Poland had fifteen Yiddish theatres and theatrical groups. Warsaw was home to the most important Yiddish theater troupe of the time, the Vilna Troupe, which staged the first performance of The Dybbuk in 1920 at the Elyseum Theatre. Some future Israeli leaders studied at University of Warsaw, including Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir.

There also were several Jewish sports clubs, with some of them, such as Hasmonea Lwow and Jutrzenka Kraków, winning promotion to the Polish First Football League. A Polish-Jewish footballer, Józef Klotz, scored the first ever goal for the Poland national football team. Another athlete, Alojzy Ehrlich, won several medals in the table-tennis tournaments. Many of these clubs belonged to the Maccabi World Union.

Kristallnacht (German pronunciation: [kʁɪsˈtalnaχt] (listen)) or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November Pogrom(s) (German: Novemberpogrome, pronounced [noˈvɛm.bɐ.poˌɡʁoːmə] (listen)),[1][2] was a pogrom against Jews carried out by SA paramilitary forces and civilians throughout Nazi Germany on 9–10 November 1938. The German authorities looked on without intervening.[3] The name Kristallnacht ("Crystal Night") comes from the shards of broken glass that littered the streets after the windows of Jewish-owned stores, buildings and synagogues were smashed. The pretext for the attacks was the assassination of the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath[4] by Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old German-born Polish Jew living in Paris.

Jewish homes, hospitals and schools were ransacked as attackers demolished buildings with sledgehammers.[5] Rioters destroyed 267 synagogues throughout Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland.[6] Over 7,000 Jewish businesses were damaged or destroyed,[7][8] and 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and incarcerated in concentration camps.[9] British historian Martin Gilbert wrote that no event in the history of German Jews between 1933 and 1945 was so widely reported as it was happening, and the accounts from foreign journalists working in Germany sent shockwaves around the world.[5] The Times of London observed on 11 November 1938: "No foreign propagandist bent upon blackening Germany before the world could outdo the tale of burnings and beatings, of blackguardly assaults on defenceless and innocent people, which disgraced that country yesterday."[10]

Estimates of fatalities caused by the attacks have varied. Early reports estimated that 91 Jews had been murdered.[a] Modern analysis of German scholarly sources puts the figure much higher; when deaths from post-arrest maltreatment and subsequent suicides are included, the death toll reaches the hundreds, with Richard J. Evans estimating 638 deaths by suicide.[11] Historians view Kristallnacht as a prelude to the Final Solution and the murder of six million Jews during the Holocaust.[12]

1939: Nazis forced 20,000 local Jews from Będzin, along with additional 10,000 Jews expelled from neighboring communities into the Ghetto. Of these 30,000 souls, only approximately 2,000 survived.

In this photograph, Polish Jews within the Ghetto perimeter, 1942.

The order to organize partisan groups was issued by Marshal of Poland Rydz-Smigly on 16 September 1939. The first sabotage groups were created in Warsaw on 18 September 1939. Each battalion was to choose 3 soldiers who were to sabotage enemy's war effort behind the front lines. The sabotage groups were organized before Rydz-Smigly's order was received.

The situation amongst the Polish partisans and the situation of the Polish partisans were both complicated. The founding organizations that lead to the creation of the Home Army or Armia Krajowa, also known as AK, were themselves organized in 1939. Home Army was the largest Polish partisan organization; moreover, organizations such as peasant Bataliony Chlopskie, created primarily for self--defence against the Nazi German abuse, or the armed wing of the Polish Socialist Party and most of the nationalist National Armed Forces did subordinate themselves, before the end of the World War II, to the very Home Army. The communist Gwardia Ludowa remained indifferent and even hostile towards the Home Army, and of two Jewish organizations, the Jewish Military Union did cooperate with the Home Army, when the leftist and pro-Soviet Jewish Combat Organization did not.

Both Jewish combat organizations staged the Ghetto uprising in 1943.

Armia Krajowa staged Warsaw Uprising in 1944, amongst other activities.

Bataliony Chlopskie fought mainly in Zamosc Uprising.

The Polish partisans faced many enemies. The main enemies were the Nazi Germans, Ukrainian nationalists, Lithuanian Nazi collaborators, and even the Soviets. In spite of the ideological enmity, the Home Army did launch a massive sabotage campaign after the Germans began Operation Barbarossa. Amongst other acts of sabotage, the Polish partisans damaged nearly 7,000 locomotives, over 19,000 railway cars, over 4,000 German military vehicles and built-in faults into 92,000 artillery projectiles as well as 4710 built-in faults into aircraft engines, just to mention a few and just in between 1941 and 1944.

In Ukraine and southeastern Poland, the Poles fought against the Ukrainian nationalists and UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) to protect the ethnic Poles from mass murder visited upon them during Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. They were aided, until after the war was over, by the Soviet partisans. At least 60,000 Poles lost their lives, the majority of them civilians, men, women, and children. Some of the victims were Poles of Jewish descent who had escaped from the ghetto or death camp. The majority of the Polish partisans in Ukraine assisted the invading Soviet Army. Few of them got mistreated or killed by the Soviets or the Polish communists.

In Lithuania and Belarus, after a period of initial cooperation, the Poles defended themselves against the Soviet partisans as well as fought against the Lithuanian Nazi collaborators. The Poles failed to defeat the Soviet Partisans, but did achieve a decisive victory against the Lithuanian Nazi collaborators, Battle of Murowana Oszmianka. Afterward, about half of the Polish partisans in Lithuania assisted the invading Soviet Army, and many ended up mistreated and even killed by the Soviets and the Polish communists.

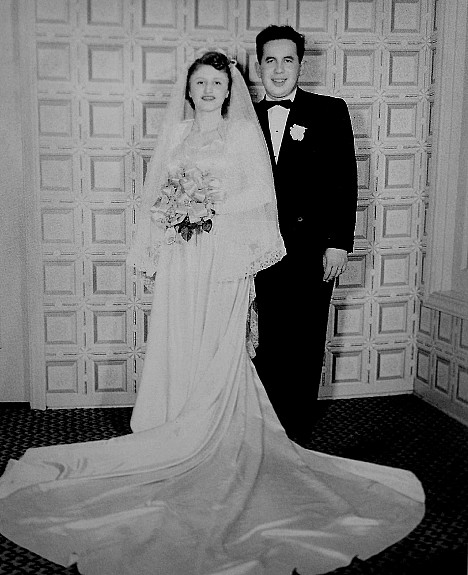

In 1949, David and Yetta separately came to Los Angeles as refugees. The following year, they met at a dance.

They married on January 19, 1952.

Hey its Emily!